If you’re a fan of the Netflix series Ozark, you’re probably already very familiar with the dangerous art of money laundering. This series does an amazing job of explaining how people who bring in large amounts of cash from an illegal source — like drugs or commercial sex — can “clean” or “launder” the money so that it looks like it came from a legitimate source. We see this activity often in trafficking operations, especially those that pose as businesses like illicit massage parlors but are making a lot of extra cash under the table. What exactly do they do with the money?

Money Laundering 101

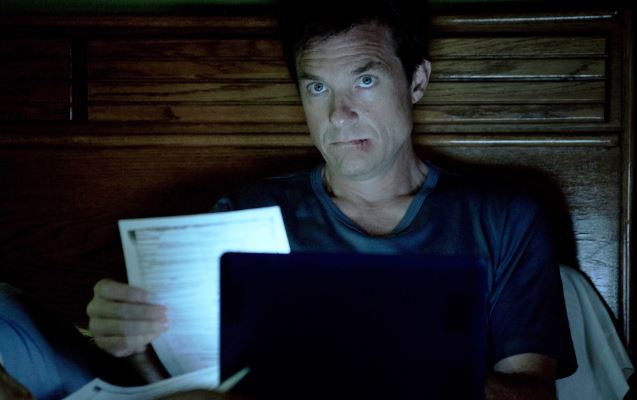

In case you are imagining a complicated washing machine only mobsters have, Jason Bateman — through his Ozark persona Marty Byrde — provides a helpful “Money Laundering 101”:

“Say you come across a suitcase with $5 million bucks in it. What would you buy? A yacht? A mansion? A sports car? Sorry, the IRS won’t let you buy anything of value with it. So you better get that money into the banking system. But here’s the problem — that dirty money is too clean. You have to make it look like it’s been around the block. You need a cash business, something pleasant and joyful, with books that are easily manipulated. You mix the $5 million with the cash from the joyful business. That mixture goes from an American bank to a bank from any country that doesn‘t have to listen to the IRS. It then goes into a standard checking account… your work is done, your money is clean.”

In Ozark, we see Bateman’s character Marty start a major money laundering operation after he comes under the threats of a cartel boss (to be fair, Marty was stealing from him). In order to save his life, Marty guarantees he can launder over $500 million in drug money in the Ozarks, a mountainous vacation spot replete with cash-rich businesses. So he packs up his well-to-do Chicago family and heads to Missouri in search of unsuspecting cash-heavy businesses he can manipulate to make good on his word.

How money laundering works in massage parlors

Human traffickers selling sex in massage parlors have the same problem on their hands as the cartel boss. Even though they’re already operating behind the storefront of a business, they still have the problem of explaining where all the extra cash is coming from. For example, “Relax Spa” may be advertising $40 an hour for massage, but accepting a $100 “tip” under the table for commercial sex. That adds up to a lot of extra money.

Massage parlor in strip mall, Tampa, FL

According to Polaris research, the massage parlor trafficking business is a $2.5 billion industry annually. How do traffickers avoid suspicion with this much money coming in? For starters, illicit massage businesses (IMBs) can hide some extra cash by altering their books internally, i.e. reporting items as costing more than they actually did and thereby laundering the money themselves.

Traffickers also wire money abroad, entirely skirting the need to clean the money for use in the United States. Some also funnel the extra money through other businesses they have in their network, such as another massage parlor, nail salon, or restaurant.

Sample massage parlor trafficking network

It all adds up

In Ozark, Marty Byrde started out with a crumbling lakeside motel, and quickly moved into the strip club and construction businesses to pick up the laundering pace. At the motel, Marty used renovations as a laundering tactic. For example, he purchased 16,000 sq. ft. of carpeting at $0.69/sq. ft., but tracked it on the motel’s accounting ledger as 32,000 sq. ft. of carpeting at $8.75/sq. ft.

That equates to $270,000 in illegal money that now looks perfectly legitimate. He then ordered four air conditioners for the motel’s rooms, but expensed 25. He made another $150,000 appear legitimate by inflating the costs of redoing the employee locker rooms.

As Marty says, money launderers are “not criminal geniuses, just pathological liars on the path of least resistance.”

This can be done anywhere. As Marty says, money launderers are “not criminal geniuses, just pathological liars on the path of least resistance.” Marty’s next move is to take over a strip club, a business where customers routinely pay in cash, and inflate the proceeds.

Hiding business ownership

The strip club is owned by a shell company (a corporation that exists in name only) to hide its true ownership. Marty’s name is conveniently nowhere on the business records. If you did some digging, you would find the club is officially owned by a company based out of Panama, linked to no individual person’s name at all.

Hiding business ownership like this is not only legal, it’s common. For Marty, such a setup provides protection by shielding him as the responsible party. Many IMB owners use shell companies for the same reason — to hide who owns their massage parlors, as well as other businesses in their networks. This makes it as difficult as possible for investigators to trace the flow of illegally-gained money and figure out who is to blame.

Marty planning his next move (source)

As described in a recent Polaris report, the United States is one of the easiest countries in the world for owners and operators of businesses to hide business ownership. Neither the federal government nor the states require companies to include the name of the “beneficial owner” (the person who actually controls the business and receives its profits) in standard registration paperwork.

Although requirements may vary slightly by jurisdiction, the owner’s name can often be left entirely blank; filled in with the name of a registered agent or other paid point of contact; or registered under the complete anonymity of an empty shell company.

Following the money

Fortunately for law enforcement, money launderers leave clues behind. By investigating money laundering, law enforcement can build cases to shut down entire networks of IMBs and their operating fronts.

Shutting down the entire trafficking network by focusing on business operations is far more effective and victim-centered than some of the typical interventions we see now — particularly raids where individual workers (potential trafficking victims) are arrested for prostitution.

Storefront massage parlor, Los Angeles, CA

Worker-focused raids do not work because the owners and operators of IMB trafficking rings, hidden behind their business anonymity, can easily recruit new victims or simply rotate them to and from other parlors in the trafficking network. The victims, meanwhile, get no relief or protection and are now at odds with the law and even more convinced of their trafficker’s prowess.

Traffickers go to great lengths to make sure that their victims fear law enforcement and are therefore unlikely to testify against them. Focusing on money laundering thwarts these manipulative efforts by removing the burden of conviction from the shoulders of victims.

Building a money laundering case is a powerful way to take down traffickers, but it requires significant time and resources. All the while Marty and his family were buying up businesses to launder money, at the risk of life and limb to those around them, the FBI was watching, waiting, and hoping to build a case. It will be interesting to see where their investigation leads in the upcoming season.