Progress for Criminal Record Relief for Survivors

In March 2019, Polaris released a report grading all 50 states and D.C. on the effectiveness and completeness of their laws allowing survivors of human trafficking to clear criminal records they have as a result of their trafficking. In 2023, we updated that report with a revised rubric to better explain what states have done and still may want to do to enact or improve criminal record relief statutes for trafficking survivors.

“After the conviction was on my record, all doors seemed to be closed for me. I lived in a prison. People might say it was in my mind, but it really wasn’t. It was reality.”

— Human Trafficking Survivor

Major Changes and Updates

Polaris and our survivor partners are gratified at the significant improvements made to laws around the country and excited to work with partners to help move additional change forward. At the time of the report in 2019, 10 states had no criminal record relief for trafficking survivors or relief that only applied to survivors arrested as minors. As of spring 2023, only five states still have no relief for adult trafficking survivors. Other states have also made significant progress in making existing laws more helpful and effective for survivors. Click on the state to view additional information.

Burden of Criminal Records

The first time trafficking survivors come into contact with law enforcementis often as an offender, not as a victim. Sex trafficking victims are commonly arrested for prostitution or for other crimes. Labor traffickers may force their victims to manufacture or sell drugs, or carry false identification. A criminal record has a profound impact on the ability of any individual to obtain gainful employment, find affordable, safe housing, and continue their education, among other things.

National Survivor Study Confirms Impact of Criminal Record

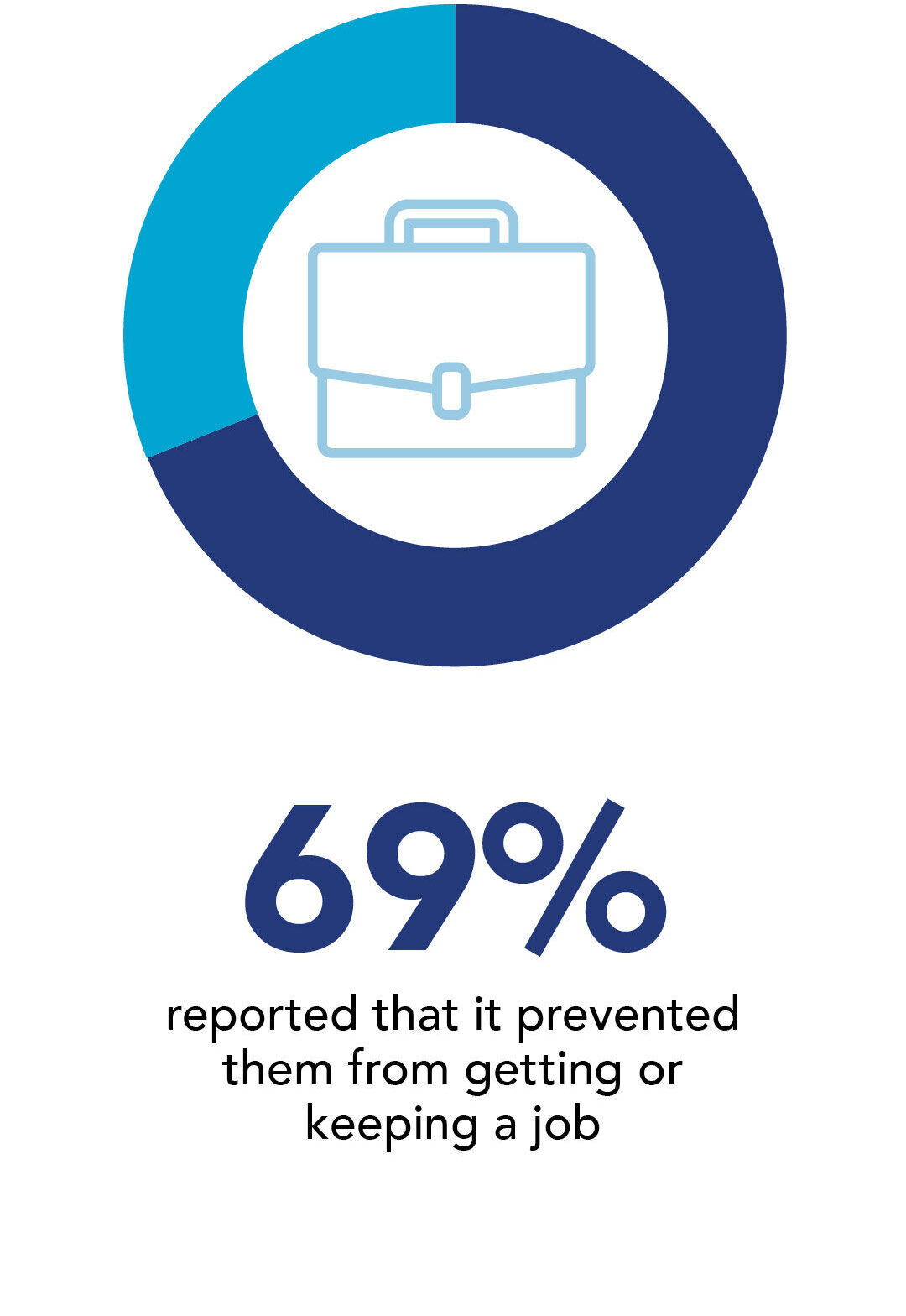

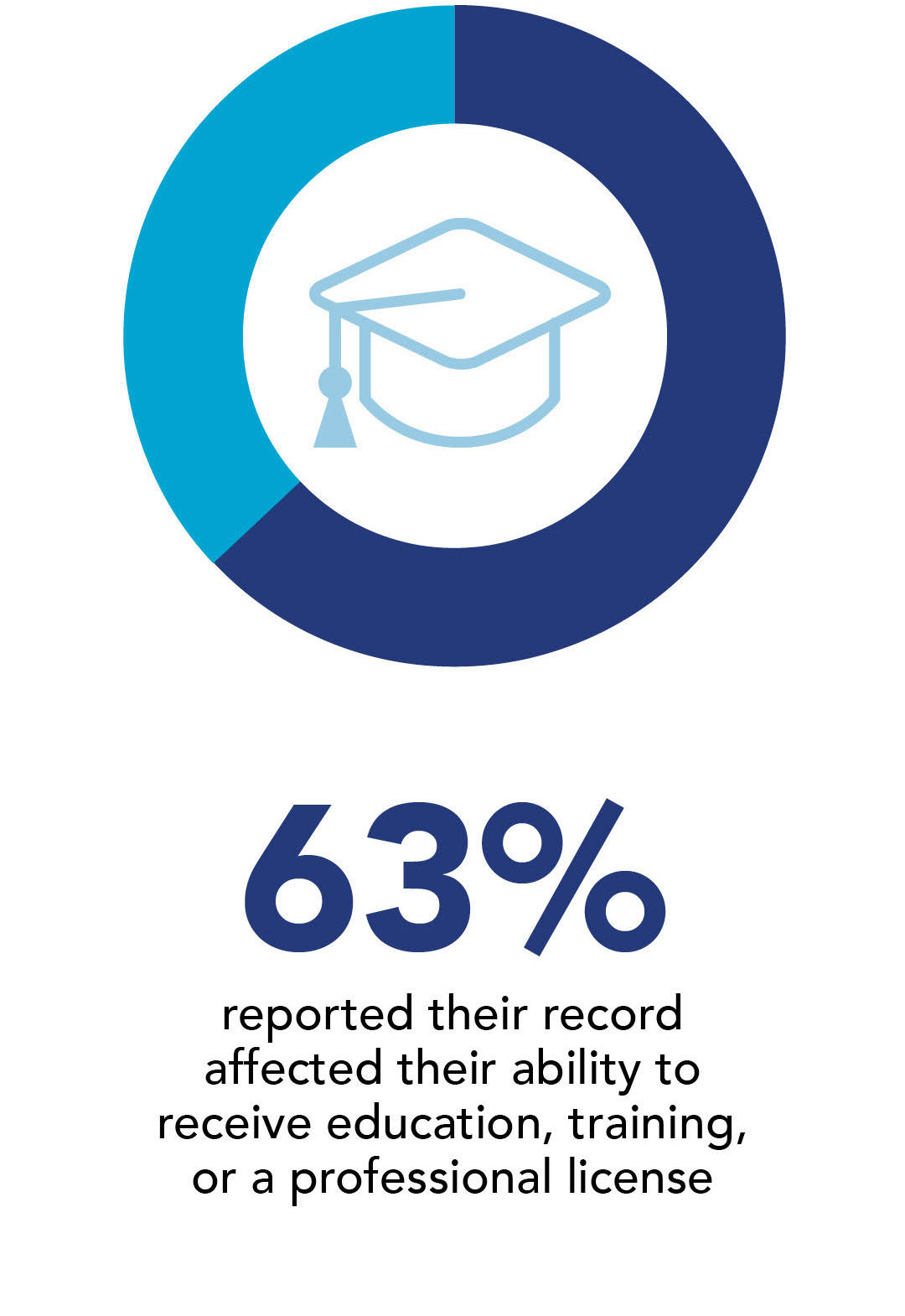

As part of the National Survivor Study, a research partnership with survivors, Polaris conducted online and phone surveys with 457 sex and labor trafficking survivors. The study found that for a majority of survivors, their criminal record created barriers to gainful employment, find safe housing, continue their education, and child custody.

Survivors Share Their Experiences

Jessica was 17 when her trafficker — the man she would have called her boyfriend — turned her out to sell sex and support him. She was traded to other pimps, moved from state to state, and racked up a string of prostitution-related misdemeanors and DUIs as a result of her trafficking. Today, Jessica is raising her family in Idaho and working to clear these charges from her record so she can rent a home for them. She is still in transitional housing with her family because with her record, many landlords won’t rent to her. Jessica, like many trafficking survivors, is caught in an ironic loop. She needs money — a lot of it — to cover the cost of clearing her record in multiple states. Yet the fact that she has a record makes it difficult or impossible for her to get a job that would allow her to earn that money. Already she has paid $2,500 to clear fines and pay for legal help for charges in California, and she can’t do anything about charges in Iowa until she pays off $700 in fines. These fines are the result of convictions that logically never should have happened, since Jessica was a trafficking victim, under the control of someone else.

Keyana Marshall is a trafficking survivor. Her story is in many ways typical of the thousands of vulnerable young people who are targeted, groomed, manipulated, addicted, dehumanized, and then sold while still not old enough to drive or vote. But hers has an additional layer of horror. In the eyes of the law, Keyana is considered a trafficker herself. She served time in federal prison for conspiracy charges she obtained while being abused in pimp-controlled exploitation.

Keyana and her husband recently moved to Ohio so she could work with a program supporting other survivors of sex trafficking. She is also working on developing her own survivor-led organization called “We Survived.” This organization will support survivors and give them resources to navigate in many different areas of life. Keyana wants to support survivors’ journeys in academia, entrepreneurship, and community re-entry.

In any state Keyana lives in or visits, she is required to register as a sex offender. She feels this has stifled her ability to flourish in the community and limits employment opportunities. “I have been threatened, denied employment, and stigmatized on this sex offender registry. I was exploited, and I couldn’t choose who my trafficker exploited. I was charged with conspiracy to commit sex trafficking of children. This forced me onto a sex offender registry three years after I was released from federal custody. I didn’t do anything wrong. My abuser forced me to post ads online, pay the phone bills, and get his cars fixed. Those actions were enough to land me in prison. I am still facing many hardships, and I’m still being punished for being exploited,” Keyana explains in frustration.

Kia was 15 and trying to survive in foster care when she was first trafficked. She grew up in a tough environment and often found herself in physical altercations with others while trying to protect herself. As a result, Kia developed a juvenile record, which expanded to a string of DUI and prostitution-related charges connected to her trafficking situation as an adult. The transient nature of Kia’s trafficking situation made it impossible for her to keep up with paperwork and information about the charges she was facing and any upcoming court appearances. Several years after leaving her trafficking situation, Kia often works multiple jobs to support herself but continues to have her wages garnished to repay fees and fines as a result of charges she incurred while in her trafficking situation. The financial burden as a result of her criminal record has made it difficult for Kia to reach out for legal assistance in clearing her record, as most of the attorneys she has encountered have charged for initial consultations or services. Kia’s criminal record has hindered her career aspirations by preventing her from pursuing roles where she can use her expertise and experience as a survivor to work directly with at-risk youth and other survivors of trafficking.

Additional Recommendations

Enacting new legislation or amending existing laws is the first and most important step toward creating a consistent and fair system that supports survivors of human trafficking as they seek to clear criminal records. But the work of supporting survivors does not end with the passage of a law. There must also be consistent and reasonable implementing regulations, data collection, and financial resources available so that we can learn what works and make additional improvements and corrections along the way.

1. Institute comprehensive data collection processes.

While the anti-trafficking field has made progress on data collection, there is still almost no information available on the utilization of state criminal record reliefs law for trafficking.

2. Ensure funding for criminal record relief legal support.

If survivors can’t afford to pay for lawyers, they often just give up, or don’t even get started, in the process of trying to clear their record.

3. Design trauma-informed implementing regulations.

Even the strongest laws on paper can become the least effective in practice if the implementing regulations — the logistical and procedural steps — are so onerous that survivors ultimately choose not to pursue relief.

4. Allocate state and local resources for outreach and awareness for survivors.

While the necessary first step is enacting strong laws or amending weak ones, those laws will make little difference without a concerted effort to let survivors know this process is available to them.