By its very nature, the crime of human trafficking involves compelling a person to do something they would not otherwise necessarily have done on their own. In the real world, that often means that survivors of human trafficking have criminal records because they were forced into commercial sex, or drug sales, or other offenses. Many, but not all states have recognized that this is fundamentally unfair and that survivors of human trafficking deserve the chance to have those records cleared. Unfortunately, the laws that do exist are badly flawed and some states have no laws at all or laws that are only available to people who were minors at the time of their trafficking.

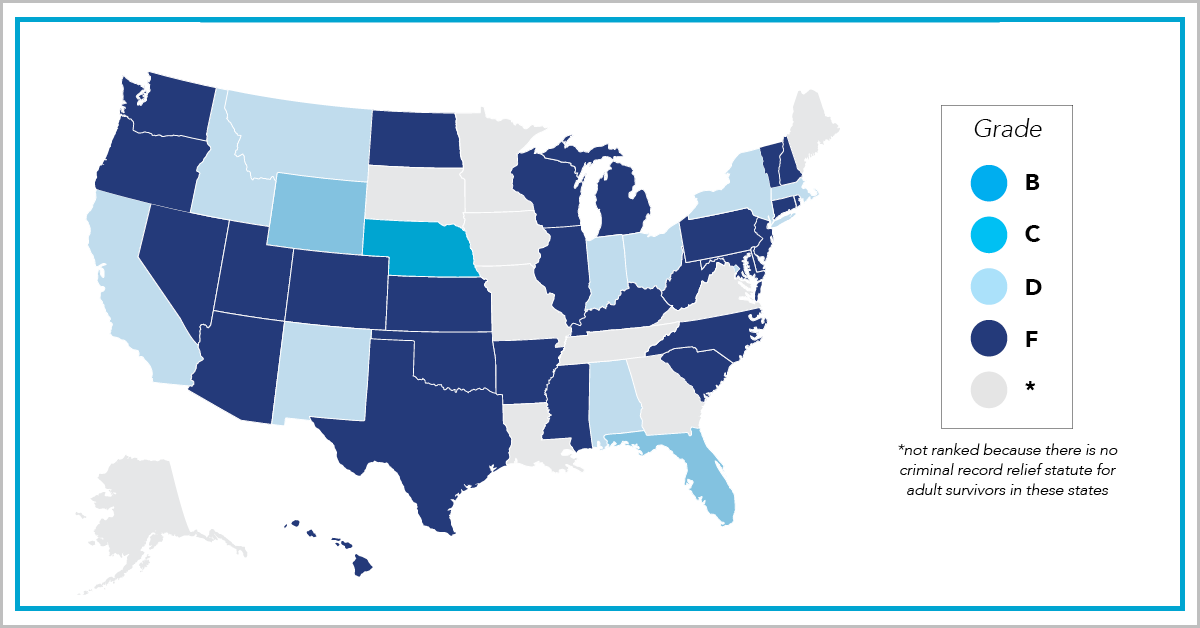

State Report Card: Grading Criminal Record Relief Laws for Survivors of Human Trafficking gives letter grades for these laws – or lack thereof – to all 50 states and the District of Columbia. The goal of the report and report cards is to make it easier for states to amend existing laws and enact new ones that truly provide a path for survivors looking to close out one chapter in their lives and begin a new one in true, legal freedom.

While there is no nationwide data on how many trafficking survivors have a criminal record as a result of their victimization, people in trafficking situations are frequently arrested, detained, prosecuted, convicted, and in some cases, incarcerated or deported, without ever being identified as a victim of human trafficking by the criminal legal system. In 2016, the National Survivor Network (NSN) conducted a groundbreaking survey on the impact of criminal arrest and detention on survivors of human trafficking. They found that 91 percent of 130 trafficking survivor respondents reported having been arrested.

Generally, the first time trafficking survivors come into contact with law enforcement are as offenders, not victims. Trafficking victims can be arrested for prostitution, or for other crimes such as possession of weapons, drugs, or identity theft — all of which likely have been orchestrated in some way by their trafficker. A criminal record has a profound impact on the ability of any individual to obtain future gainful employment, find affordable and safe housing, be able to begin or continue their education at college, obtain financial aid for tuition, retain custody of their children, and can affect an individual’s access to crucial government benefits. For foreign national survivors, their ability to remain and/or work in the United States depends greatly on their criminal record.

The following story is from one trafficking survivor who spoke on her experience fighting for criminal record relief and how her criminal record held her back from rebuilding her life after her trafficking experience. Her story illustrates the importance of states having criminal record relief for trafficking survivors.

Sara* grew up with parents who had mental illness and who forced her out of her home as a teenager. Without guidance, she did not go to college after high school and moved across the country with her boyfriend. He later turned out to be abusive and threw all of her clothes away. She escaped from him and began working two jobs, but she was still without a car and basic necessities. Working as an exotic dancer seemed to be the only way to get herself out of poverty. At the club where she worked, a couple befriended her. They were kind at first but then isolated her and manipulated her into going up to a hotel room to sell sex. She did not want to do it, but did not see a way out of the situation. The very first time they sent her out she was arrested by an undercover police officer on prostitution charges. “Police didn’t ask me anything. I tried to tell them what was going on and they just said I was a liar, and were rough with me,” she remembers. With no one to post bail for her, her best option was to plead guilty or face three months of waiting in jail. Knowing that she couldn’t afford to stay in jail — it would mean losing her car and all of her belongings — she pleaded guilty and was convicted of a misdemeanor. She still spent about two weeks in jail.

“After the conviction was on my record, all doors seemed to close for me. I lived in a prison,” says Sara. “People might say it was in my mind, but it really wasn’t. It was reality.” Applying for jobs, applying for school, trying to get an apartment — anything involving a potential background check — was loaded with stress and anxiety. She said, “I know I would have stopped dancing after I got away from the couple that tried to traffick me, but with the conviction I felt I had no other option but to continue working as a dancer and living in the shadows.”

When Sara went to see if she could do anything to get the conviction off of her record, she found out that there were no options for her. The State of Florida would only help those who had an adjudication of guilt withheld, not a conviction. Because she had pleaded guilty, she had a conviction on her record and zero options.

“It’s a horrible, horrible thing to live with; a secret that’s over your head all the time. You can’t really tell anybody why you aren’t applying for this job, or going for that opportunity” explains Sara. “I basically ran from this for the next 20 years.”

She spent the next eleven years working as a dancer, before enrolling in community college, followed by a four-year college. All the while, she pressured herself to work harder and achieve more than everybody else, knowing that when the time came to apply for jobs, employers would see her conviction. She had to do everything possible to make sure they would want to hire her despite her criminal record. She got straight A’s, won scholarships, and was chosen for prestigious internships. Reflecting on the honor of being selected as graduation speaker for her department, Sara thought, “there I was, standing up in front of my whole class, and they didn’t know I had this horrible secret.”

As a new graduate, applying for jobs meant anxiously wondering whether the question on the application would read “have you ever been convicted of a crime” or “have you been convicted of a crime in the past seven years.” She always prayed for the latter, as the former would mean a humiliating revelation. Luckily, in 2010 Sara was recruited to a major company that only asked about the last seven years. She finally had her first real job in the corporate world.

Unfortunately, 2010 was also the year that the Florida county where she was arrested decided to publish all arrests with booking photos on their website. While the county website was not searchable by Google, websites like Mugshots.com quickly started to share the photo hoping for a profit. Now, if anybody Googled Sara’s name, the top result would be her mugshot. Her anxiety went through the roof. Only for a fee — often several hundred dollars — would the websites agree to take it down. Having panic attacks, Sara started paying one website after another, trying to get control of her internet presence. She could not believe she was being extorted and there was no legal recourse, nobody that could help. “It was excruciating, I felt let down by lawmakers, but there was just nobody to reach out to,” Sara recalled. After about $5,000 in payments with no end in sight, she contemplated killing herself. She finally decided that her only option was to legally change her name, which she did.

In 2015, she heard on the radio that the federal government had passed a law requiring states to implement procedures for legal relief for victims of trafficking. She was in the car with friends who heard the same story but to them, this was just a random piece of news. Nobody knew how much it might affect her life. She felt alone and ashamed.

It took Sara until 2017 to build up the courage to reach out to a Florida anti-trafficking organization who then referred her to an attorney. Living in California at the time, Sara was able to handle everything remotely. She filled out extensive paperwork, answering intensely personal questions. “I felt like I was being interrogated. They were digging up really traumatic information, trying to determine if I was lying or not. I’m grateful that the state has a process now… but it’s a horrible process.” The final step was a video interview with the state attorney’s office. Luckily, her lawyer was able to connect Sara with a local organization in California, that supported her through the emotionally difficult call. One long month later, she received the decision: after 20 years and 6 months, her record would finally be vacated.

Sara still feels resentment towards the justice system for all of her missed opportunities over the years, but things are significantly better now. She says, “I used to obsess about my conviction, constantly replaying the situations and the people who trafficked me in my mind. I could never heal from my trafficking experience. But from the day my record was vacated, I never thought about it again.”